申し訳ありませんが、Prediction Marketsが「真実の機械」となったことは一度もありません

予測市場が物議を醸すたびに、私たちは一つの核心的な問いに戻ります——しかし、その問いに正面から向き合うことはほとんどありません。

予測市場は本当に「真実」を扱っているのでしょうか?

ここで問われているのは、正確性や有用性、世論調査やジャーナリスト、SNSの世論より優れているかどうかではありません。根本的な論点は、「真実」そのものです。

予測市場は、まだ起きていない事象に価格を付けます。事実を報告するのではなく、未確定で不確実、かつ知り得ない未来に確率を割り当てます。そして、いつしか私たちはこれらの確率を一種の「真実」として扱い始めました。

この1年の大半、予測市場は「勝利の凱旋」を享受してきました。

世論調査やケーブルニュース、さらにはPowerPointを使う専門家よりも優れた成果を上げています。2024年の米国選挙サイクルでは、Polymarketのようなプラットフォームがほぼすべての主流予測ツールよりも早く現実を反映しました。この成功は新たな物語となり、予測市場は単に正確なだけでなく、より純粋な「真実の集約手段」であり、人々の信念をより忠実に映す「シグナル」だと語られるようになりました。

そして1月が到来します。

Polymarketに新規アカウントが現れ、ベネズエラ大統領ニコラス・マドゥロが月末までに失脚するという賭けに約$30,000を投じました。当時、市場はこの結果に極めて低い確率——一桁台しか付けていませんでした。負ける賭けに見えました。

数時間後、米国当局がマドゥロを逮捕し、犯罪容疑でニューヨークに連行しました。このアカウントはポジションをクローズし、$400,000超の利益を得ました。

市場は「正しかった」のです。

そして、まさにそれが問題なのです。

支持者はしばしば予測市場について安心感のあるストーリーを語ります:

市場は分散した情報を集約します。異なる見解を持つ人々が自らの信念に資金を投じ、証拠が積み重なるにつれて価格が動きます。集団は徐々に「真実」に収束していきます。

この物語は重要な前提を仮定しています。市場に入る情報が公開されていてノイズが多く、確率的である——世論調査の動向、候補者の失言、進路を変える嵐、業績未達の企業などのように。

しかし、マドゥロ取引は異なりました。それは推論よりも「完璧なタイミング」に依存していました。

その瞬間、予測市場は巧妙な予測ツールというより、別のもの——アクセスが洞察に勝り、解釈よりもコネクションが重要な場所——のように見え始めました。

もし市場の正確性が、他者には得られず知り得ない情報を持つ誰かに依存しているなら、市場は「真実」を発見しているのではなく、「情報の非対称性」を収益化しているのです。

この違いは、業界が一般的に認めているよりもはるかに重大です。

正確性は警告サインとなり得ます。批判に直面すると、予測市場の擁護者はよくこう主張します:インサイダーが取引すれば、市場はより早く反応し、皆に利益をもたらす。インサイダー取引は「真実」の開示を加速する、と。

この理論は明快に聞こえますが、実際には論理が崩壊します。

もし市場の正確性が、軍事作戦のリークや機密情報、政府内部のスケジュールなどに由来するなら、それはもはや公開情報市場ではありません。秘密取引のための「影の場」と化します。優れた分析力への報酬と、権力への近さへの報酬は本質的に異なります。この線引きを曖昧にした市場は、正確性が理由で規制当局の監視対象となるのです——不正確だからではなく、不適切な理由で「過度に正確」だからです。

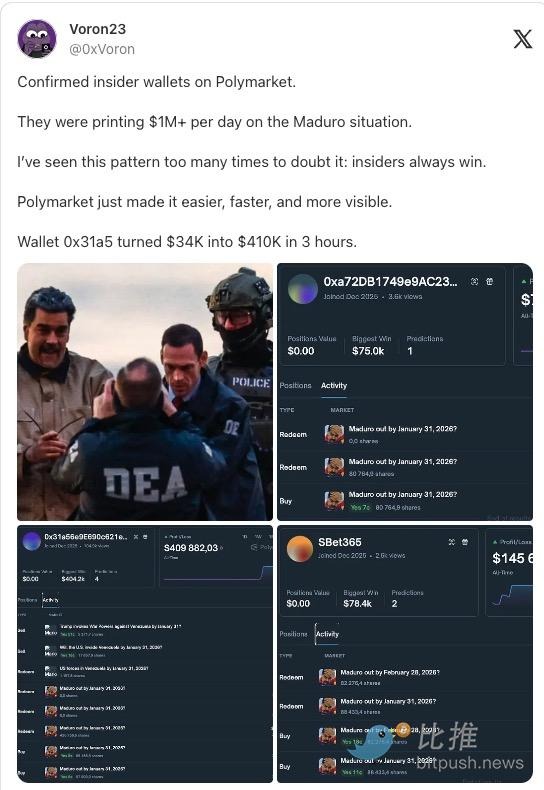

Voron23 @ 0xVoron Polymarketでインサイダーと確認されたウォレット。

「彼らはマドゥロ案件で1日で$1,000,000超の利益を上げた。

このパターンは何度も見てきた——インサイダーは常に勝つ。

Polymarketは、より簡単に、より速く、より可視化しただけだ。

ウォレット0x31a5は$34,000を3時間で$410,000にした。」

マドゥロ案件の問題点は、利益の規模だけでなく、こうした市場が急成長している背景そのものにあります。

予測市場は、周縁的な珍奇さからウォール街も真剣に受け止める独立した金融エコシステムへと進化しました。2023年12月のBloomberg Markets調査によれば、伝統的なトレーダーや機関投資家は、予測市場を持続可能な金融商品と見なしていますが、これらのプラットフォームは「ギャンブル」と「投資」の境界を曖昧にしているとも認めています。

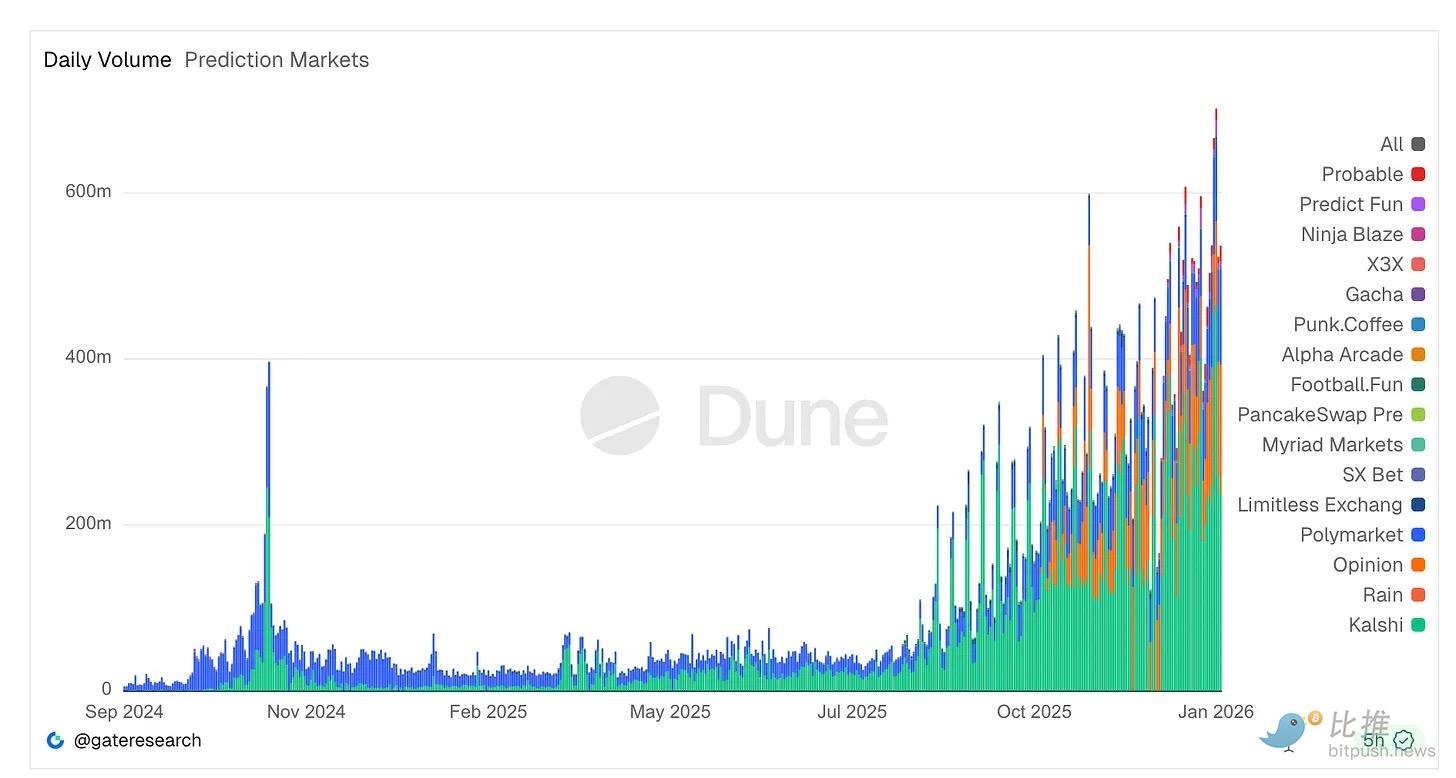

取引量は急増しています。KalshiやPolymarketなどのプラットフォームは、年間で数百億ドル規模の名目取引を記録しており、Kalshi単体で2025年には$24,000,000,000近くを処理しました。政治やスポーツ契約にかつてない流動性が集まり、日々取引記録が更新されています。

監視が強まる中でも、予測市場の1日あたり取引高は過去最高を記録し、約$700,000,000に達しています。規制されたKalshiのようなプラットフォームが取引量を牽引し、暗号資産系プラットフォームは文化的中心に位置しています。新たなターミナルやアグリゲーター、分析ツールも毎週登場しています。

この成長は、巨大な金融資本を呼び込みました。ニューヨーク証券取引所の親会社は、Polymarketとの戦略的取引に最大$2,000,000,000をコミットし、同社の評価額は約$9,000,000,000に達しています——ウォール街がこれらの市場を伝統的な取引所と競合できると見ている証拠です。

しかし、このブームは規制・倫理のグレーゾーンと衝突しています。Polymarketは初期に未登録営業で禁止され、CFTCに$1,400,000の罰金を支払いましたが、最近になって米国で条件付き承認を得たばかりです。一方、リッチー・トーレス下院議員は、マドゥロ案件の支払いを受けて政府インサイダーの取引を禁止する法案を提出しました。これは、情報に基づく投機というより、事前取引の機会に見えたと主張しています。

それでも、法的・政治的・評判上のプレッシャーにかかわらず、市場参加は減少していません。むしろ、予測市場はスポーツベッティングから企業業績など新領域へ拡大し、伝統的なギャンブル会社やヘッジファンドも専門家を配置して裁定取引や価格の非効率性を突くようになっています。

要するに、これらの動向は予測市場がもはや周縁的存在ではないことを示しています。金融インフラとの結びつきを強め、プロ資本を呼び込み、新たな法規制を促しつつ、その本質は「不確実な未来への賭け」であり続けています。

見落とされた警告:ゼレンスキー・スーツ事件

マドゥロ事件がインサイダー問題を露呈したなら、ゼレンスキー・スーツ市場はさらに深い問題を示しました。

2025年半ば、Polymarketはウクライナ大統領ヴォロディミル・ゼレンスキーが7月までにスーツを着るかどうかの市場を開設しました。数億ドル規模の取引が集まりました。冗談のような市場が、急速にガバナンス危機へと発展しました。

ゼレンスキーは有名メンズウェアデザイナーによる黒のジャケットとスラックス姿で登場しました。メディアもファッション専門家も「スーツ」と呼び、誰が見てもそうでした。

しかし、オラクル投票の裁定は「スーツではない」でした。

なぜでしょう?

答えはこうです:一部の大口トークン保有者が反対の結果に巨額の賭けを行い、十分な投票権で自分たちに有利な裁定を通したのです。オラクルを買収するコストは、彼らの潜在的な配当よりも低かったのです。

これは分散化の失敗ではなく、インセンティブ設計の失敗です。システムはコード通りに機能しました——人間駆動のオラクルの誠実さは「嘘をつくコスト」に完全に依存します。この場合、嘘をつく方が利益になったのです。

こうした出来事を、単なる例外や成長痛、より良い予測システムへの一時的な不具合と見るのは簡単です。しかし、それは誤解です。これらは偶然ではなく、金融インセンティブ、曖昧なルール定義、未成熟なガバナンスの3要素が必然的に生む結果です。

予測市場は「真実」を明らかにするのではなく、単に「決済結果」を生み出すだけです。

重要なのは、多数派の信念ではなく、最終的にシステムが有効な結果と認めるものです。そのプロセスは意味論、権力闘争、資本のゲームが交錯する場所にあります。巨額の資金が動くと、その交差点はすぐに利害対立で満たされます。

これを理解すれば、こうした紛争ももはや驚きではありません。

規制は突然生まれるものではない

マドゥロ取引への立法対応は予想通りでした。現在、連邦職員や公務員が重要な非公開情報を持ったまま政治予測市場で取引することを禁止する法案が議会を通過中です。これは過激な措置ではなく、基本的なルールです。

株式市場は何十年も前にこれを理解しました。政府関係者が国家権力への特権的アクセスから利益を得るべきではない——これは標準です。予測市場が今これに直面しているのは、あたかも別物であるかのように装ってきたからに他なりません。

私たちはこの問題を複雑にしすぎました。

予測市場は、まだ起こっていない結果に賭ける場にすぎません。イベントが自分に有利に動けば利益を得、そうでなければ損失を被ります。その他は全て物語にすぎません。

洗練されたUIや確率表現で「別物」になるわけではありません。ブロックチェーン上で動作していても、経済学者向けにデータを生成していても、より「真剣」になるわけではありません。

重要なのは「インセンティブ」です。報酬は洞察力ではなく、「次に何が起こるか」を当てることに支払われます。

高尚な何かに仕立て上げようとするのは不要です。予測や情報発見と呼んでも、リスクやその理由は変わりません。

ある程度、私たちは認めるのをためらっているようです——人々は単に「未来に賭けたい」のです。

その通りです。それで構いません。

しかし、それ以上のものだと装うのはやめるべきです。

予測市場の成長は本質的に「ナラティブ」——選挙、戦争、文化イベント、そして現実そのもの——に賭けたいという欲求によって駆動されています。その需要は本物で、持続的です。

機関投資家は不確実性のヘッジに、個人は信念表明や娯楽に、メディアは風見鶏としてこれを利用します。いずれも偽装は不要です。

実際、偽装こそが摩擦を生みます。

プラットフォームが自らを「真実の機械」と称し、道徳的優位を主張すれば、あらゆる論争が「存在論的」なものとなります。市場が不穏な形で決済されれば、それは哲学的なジレンマとなり、本来の「ハイリスクなベッティング商品の決済を巡る紛争」ではなくなってしまいます。

誤った期待は、不誠実な物語から生まれます。

私は予測市場に反対ではありません。

予測市場は、人間が不確実性下で信念を表明する、より誠実な手段の一つです——しばしば世論調査よりも不都合なシグナルを早く浮かび上がらせます。今後も成長は続くでしょう。

しかし、これを高尚なものに祭り上げるのは自己欺瞞です。予測市場は認識論的なエンジンではなく、「未来の出来事に紐づいた金融商品」です。この区別を認めることで、より健全な市場となり、明確な規制や倫理、優れた設計に繋がります。

自分がベッティング商品を運営していると認めれば、その中でベッティング行動が起きても驚かないはずです。

免責事項:

- 本記事は[BitpushNews]より転載したものであり、著作権は原著者[Thejaswini M A]に帰属します。本転載にご懸念がある場合は、Gate Learnチームまでご連絡ください。関連手続きに従い速やかに対応いたします。

- 免責事項:本記事に記載された見解や意見は著者個人のものであり、投資助言を構成するものではありません。

- 本記事の他言語版はGate Learnチームが翻訳したものです。Gateの記載がない限り、翻訳記事の無断転載・配布・盗用を禁じます。

関連記事

ステーブルコインとは何ですか?

ブロックチェーンについて知っておくべきことすべて

Cotiとは? COTIについて知っておくべきことすべて

分散型台帳技術(DLT)とは何ですか?